...from all of us at the Northampton Speculative Fiction Writers Group to the readers of this blog.

Happy Christmas and our best wishes for the New Year.

The blog - with its articles, news and various lists - will be back in January, starting with a round-up of the year from co-chairman Ian Whates, followed by some writing advice from NSFWG chairman Ian Watson.

See you in 2014!

Tuesday, 10 December 2013

Monday, 2 December 2013

Creature From The Black Lagoon, a review by Mark West

Following on from Ian Watson's article about "Moon" and "Sunshine" a few weeks ago, here is an article/review from NSFWG member Mark West on the classic 1954 Universal horror film.

As a child of the 70s and 80s, I grew up without ready access to the films that I read about in magazines or books and so a lot of my exposure to early horror was if I was allowed to stay up late on a Saturday night to watch one. Then, during one summer – I think it would be been 1980 or 1981 – a lot of classic B&W chillers were shown on BBC2, after tea. Finally, I got to see Lon Chaney as The Phantom, rather than just reading about him and scaring myself silly over the pictures; finally I got to witness Boris Karloff’s superb performance as Frankenstein’s monster and finally, I got to see the creature that, for me, is the highpoint of Universal horror icons.

Assuming it was 1981, I was twelve when I first saw “Creature From The Black Lagoon” and I loved it. I bought the DVD, years later and watching it again is like revisiting a much-loved old friend.

Opening with a prologue that details the formation of earth (but, really, is just an excuse to have loads of things hurtling at the camera to fully utilise the 3D experience), this moves to the present day where a geology expedition in the Amazon uncovers a fossilised hand from the Devonian (I don’t know either) period. The expedition leader, Dr Carl Maia (Antonio Moreno) takes it to his friend, Dr David Reed (Richard Carlson), an ichthyologist and the formers girlfriend Kay Lawrence (Julia Adams). Their financial backer, Dr Mark Williams (Richard Denning), decides to fund an expedition so they sail up the Amazon in an old steamer called Rita, captained by Lucas (Nestor Paiva).

Arriving at Maia’s camp, they discover his workers dead (we, the viewer, get to see the attack, where the Gill-Man is threatened and so fights back) and decide to stay on to look for more fossils. Reed suggests that some rock formations could have been washed downriver and Lucas tells them of the “Black Lagoon”, a paradise from which no-one has returned, where the tributary they are on ends. They set off, unaware that the Gill-Man is watching them, as it’s spotted Kay and likes what he’s seen.

Once at the Lagoon, Reed and Williams go scuba-diving and pick up some samples and then, whilst they’re examining them, Kay goes for a swim and the Gill-Man stalks her, touching her feet with an almost gentle reverence. It then gets caught in the ships net but escapes, accidentally leaving behind a claw to reveal its existence.

After killing two of Lucas’ crew members, the Gill-Man is captured and locked in a cage on the Rita. It escapes and Reed decides that they should return to civilisation but the Gill-Man has other ideas and blocks the lagoon entrance with logs. As the crew attempt to move them, Williams is killed by the creature, who then abducts Kay to take back to his cave. Reed, Lucas and Maia follow, rescuing her and shooting the creature. He is last seen sinking slowly into the depths, presumed dead.

This is a terrifically entertaining film and I really enjoyed it. Ably directed by Jack Arnold (who made, amongst many others, “It Came From Outer Space”, “Revenge Of The Creature”, “Tarantula”, “The Incredible Shrinking Man” and “Monster On The Campus”, before moving into TV directing), this keeps up a good pace from the off, with only a couple of slower moments which mainly seem to do with the 3D experience. The writing, by Harry Essex and Arthur Ross, keeps the scientific mumbo-jumbo to a minimum, though I could have done without the “Devonian period” and whilst it’s a fairly standard plot, the character interplay is sharp and bouncy. The production design is terrific, with the main set being Rita in the lagoon and whilst we never see the whole area, you get the sense of the claustrophobia, which ramps up the suspense when the Gill-Man is on the prowl.

The acting is, on the whole, pretty good with Nestor Paiva making the most of his character’s cheerful brashness to hold the screen whenever he’s on, whilst Richard Denning seems to relish his characters nastiness. Julia Adams, the beauty to the Gill-Man’s beast, is more than just decoration, holding her own even when – at times – she’s reduced to simply being the person who screams to alert the others. As for the Gill-Man himself, the two stuntmen who played him – Ben Chapman on land, in a darker suit and Ricou Browning underwater, in a lighter suit – aren’t credited in the film, which is a shame.

The underwater sequences, directed by James C Haven, are beautifully photographed, with the murky depths illuminated by shafts of sunlight that look spectacular. Arnold spends a good chunk of the running time underwater, highlighting the differences in the worlds though some of the swim-pasts, though they probably looked great, feel like padding in 2D.

Of course, a monster movie lives or dies by the quality of its “star” and this doesn’t disappoint. Apparently stemming from a story the producer William Alland was told, about a mythical race of half-man/half-fish creatures in the Amazon, this introduces the Gill-Man early and doesn’t suffer for it. He even gets his own theme – some jangling horns – and the first ‘shock’ reveal of him, underwater, is still quite unnerving today.

A big element of that is the fantastic suit, though it wasn’t without its disadvantages, visibility being one of them. Chapman apparently bashed Julia Adams’ head as he carried her into the cave and Browning had to hold his breath for long periods of time, so that all the air had left the suit before he could move. Designed by Millicent Patrick, though Bud Westmore took the credit, the creature’s facial features were based on a frog, hence the bulging jowls as it breathes. With scales and fins and hands like a wicket keepers gloves, the suit looks superb – on land or in water – and still holds up well when viewed now (as it should, costing $12,000 back then).

This was originally shown in 3D (the director also made “House Of Wax” the previous year, another 3D film), as was the craze at the time but I’ve never seen it in that format and some of the ‘special dimensional effects’ get a bit wearing when watched in 2D. But as a quibble, it’s very minor.

The film was successful enough that two sequels followed – “Revenge Of The Creature” (1955) and “The Creature Walks Among Us” (1956).

“Creature From The Black Lagoon” is a classic, giving the genre at least two highly iconographic images – the Gill-Man himself and the wonderful underwater swimming session with the lovely Julia Adams, sparkling in her white one-piece. What makes the character stronger is that, in the end, he’s a sympathetic creature – he’s only trying to protect himself and his environment from the deadly encroachment of men.

This is a cracking film and very highly recommended.

This review was first published at the Monster Awareness Month website in February 2011

Monday, 25 November 2013

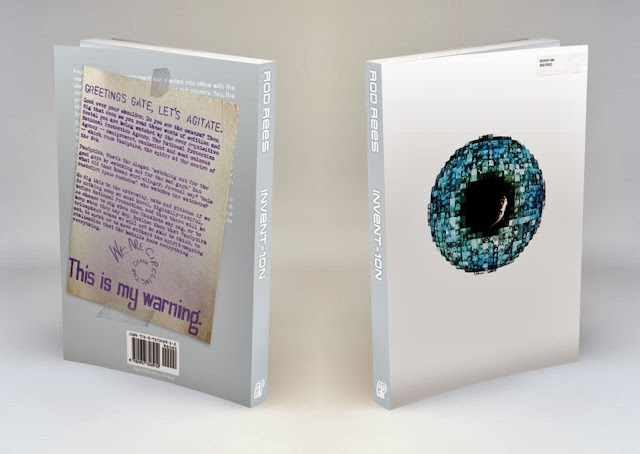

Invent-10n - a new novella by Rod Rees

INVENT-10n

You

know they’re watching, don’t you?

Invent-10n is my

latest book (I call it a semi-graphic novella, that’s a novel of 60,000 words

augmented with illustrations) which is to be published by Alchemy Press in December.

It’s a dystopian story, following the travails of my heroine – twenty-year old jive-talking,

nuBop singer and angry young lady, Jenni-Fur – as she struggles against the

suffocating strictures of the surveillance society that is Britain 2030.

Invent-10n began

life a long time ago – in 2009 to be exact – when I was playing around with the

idea of writing a story about a world where the full implications of living in

a pan-surveillance society were being played out.

My research told me that, by some margin, the British are

the most watched people on the planet with one CCTV camera for every fourteen

of us (a conservative estimate by the way). The reality is that no matter where

we are, we’re being watched. What this also signals is how obsessed the British

authorities (be they the police, security services or local councils) are with

CCTV surveillance: they have become the most avaricious voyeurs in history.

Worse, the brouhaha following Edward Snowden’s disclosures regarding GCHQ’s

Tempora system – the hacking into the transatlantic fibre-optic cables by the

British security services – indicates that the British authorities don’t just

like to watch, they like to listen too!

The chilling thing is that Tempora is one and only one of

the programs our spooks are developing to better access, store and analyse our

e-communications: they can tap into the calls you make on your cell-phone, read

what you say in the e-mails you send and monitor the opinions you post on

social media sites.

The Britain of 2030 described in Invent-10n is one where this information-gathering addiction has

reached its zenith (or its nadir, depending on your point-of-view) and my

fictional National Protection Agency – the MI5 of 2030 Britain – is using its

PanOptika surveillance system to hoover up all

personal data relating to everybody

in Britain.

Fiction did I say?

Infinitely large data storage capabilities coupled with the

use of unfeasibly powerful algorithms means that soon (as in now!) our security

services will have a real time 360⁰ portrait of each and every one of us. They

will know what you did, when you did it, who you did it with and what you said

while you were doing it … everything … 24/7. All of these data will be poured

over looking for patterns that might suggest you’re thinking of doing something

of which the government doesn’t approve.

Which brings me back to the heroine of Invent-10n, Jenni-Fur. She is a girl mindful of Scott McNealy’s

famous maxim, ‘Privacy is dead, get over it’. Jenni-Fur comes to understand

that curbing the inclination of the National Protection Agency to dig and delve

into her life is futile: knowledge is power and politicians (the putative

masters of the security services) are in the business of acquiring and wielding

power. As Jenni-Fur sees it the surveillance genie will NEVER be put back in

its lamp.

What Jenni-Fur also realises is that the availability of so

much surveillance-gathered information puts democracy at risk. This is what she

calls the ‘J. Edgar Hoover Syndrome’, where the power derived from having

access to so much (often very sensitive) information has a corrupting effect on

those controlling it. In a world supervised by PanOptika it is oh-so-easy to

follow the declension:

Yesterday the Government was

serving you …

Today the Government is surveilling you …

Tomorrow the Government will be controlling

you.

Jenni-Fur’s insight – her Ker-Ching Moment – comes when she

understands that it isn’t the computers and cameras that threaten our freedoms

but the use made of this surveillance-harvested information by the Government.

Therefore she must scheme to take the human element out of the surveillance

matrix, to use the computer to protect us from ourselves. To do this she teams

up with mysterious übergeek, Ivan Nitko, inventor of the eponymous Invent-10n.

Jenni-Fur’s world is one where paranoia is an everyday state

of mind and to communicate this I wanted to create a feeling in the mind of the

reader that they were actually in

that world so I came up with the idea of combining faux-factual material

supposedly published in the e-media of 2030 and interlacing this with extracts

from the diaries of the two chief protagonists, Jenni-Fur and National

Protection Agency apparatchik, Sebastian Davenport.

Given that there would be significant design element in the

book I collaborated with a friend of mine, Nigel Robinson, who did the artwork

for my Demi-Monde series.

That was when I got distracted writing the four Demi-Monde books and Invent-10n lay on a dongle gathering

dust. Then in March this year a friend of mine – Peter Coleborn – who I knew

from the Renegade Writers’ group in Stoke sent me an e-mail asking if I had

anything, novella-sized, I might consider publishing through his imprint,

Alchemy Press. I remembered Invent-10n

and sent a mock-up to Peter. Peter liked it (what a sensible lad!).

Now I was

faced with finishing the bloody thing … and up-dating it. In this day and age four

years is a technological eternity and reality had already caught up with some

of the ideas I’d dreamed up back in 2009. The most alarming was that in the

original Invent-10n my characters

used a thing called a Polly (a Poly-Functional Digital Device) to e-interact

with each other and Nigel had designed a Polly (in 2009) to look like this:

Seem familiar? One year later Apple came up with their iPad!

Bollocks!

For this and other reasons I had to rework/remodel Invent-10n which took longer than I

supposed – two months in fact – and then I had to hand it over to Nigel to work

his design magic. The interesting thing was while Nigel beavered away the world

became increasingly aware/interested in surveillance and its implications for

society. The Edward Snowden revelations and the realisation (pause for gasps of

surprise) the GCHQ was actually e-monitoring everybody and his brother via its Tempora

system made me more determined to finish Invent-10n

while the subject was hot. When I had written it in 2009 I had been writing a

fantasy, now it was more a piece of social commentary.

So, what with the design requirements of the book and

Peter’s various editing suggestions Invent-10n

wasn’t finally finished until early September. Then I had to write the blurb

which would go on the back of the book and wanting something suitably Jenni-Fur-esque

I came up with this (presented à la Jenni-fur on a typewriter, which she uses to

avoid the e-wigging of the National Protection Agency):

Greetings Gate, let’s Agitate.

Look over your shoulder. Do you see the camera? Then dig

that even as you read these words of sedition and denial you are being watched

by the ever e-quisitive National Protection Agency. The National Protection

Agency –

omnipresent, omniscient and most ominous –

which runs PanOptika, the spider at the centre of the Web.

PanOptika.

What’s the slogan: watching out for the

good guys

by watching out for the bad guys.

But what did that Roman word-slinger, Juvenal say? Quis

custodiet ipsos custodes: who watches

the

watchers?

So dig this to the extremity, cats and kittens: if we do

nothing soon we must kneel, digitally-dutiful, before National Protection, and

then there will be no chance to zig when the ChumBots say zag, or to beep when

they say bop. Realise thou that PanOptika triumphant means we will not be able

to think, to act, to speak or to move without the spirit-sapping realisation

that the badniks know everything …

everything.

We are circling the drain.

This

is my warning.

I hope you enjoy the book!

Rod Rees

Monday, 18 November 2013

Action, Action, Action, an article by Paul Melhuish

A few weeks ago I went to the cinema to watch Elysium. I was really looking forwards to it. Made by the same people who did the excellent District 9, Elysium promised a thought provoking premise and detailed, convincing CGI. The thought provoking premise was basically this; all the rich people went into space to live in a vast orbiting suburb that reminded me of parts of Surrey. These elite millionaires had found a cure for ALL disease and illness. Of course, they were all keeping all for themselves so struggling citizens from the poverty stricken Earth wanted to make it to Elysium and find a cure for their sick children or themselves. The protagonist gets a dose of radiation from the nasty robotics factory where he works and needs a cured in the next five days so takes a risky illegal flight to the orbiting space station.

All brilliant but then the fighting began. I sat through repeated action sequence after action sequence and this caused me to wonder if all these sequences were specifically put in to keep the audience happy.

So, what do I mean by keeping the audience happy? I’m not saying that Britain is populated by knuckle dragging morons who’s attention is only kept by action sequences and let me categorically state that I DO NOT BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE. You cannot separate our society into two fractions; those who watch documentaries on BBC4 and those who watch the X Factor. I don’t believe humanity cannot be so easily categorised. I have friends who don’t have a humanities degree and like to watch the X Factor but also understand the complex metaphysical conundra central to the plot on a programme such as Life on Mars. They understand it but don’t use pretentious phrases such as ‘metaphysical conundra’ to explain it like just did.

From my perspective that film producers seem to think that you can categorise society like this and an action sequence will bring in the masses of drooling Burberry-wearing chavs to a film like Elysium because they won’t understand the plot and a fight sequence will keep them entertained. The media always underestimates the intelligence of the average citizen.

Sci-fi, in the cinema at least, now seems to equate lots of shooting with big, futuristic looking guns. Since the space-marines in Aliens stepped out onto LV-426 back in 1987 there has followed a trail of films where space marines step onto an unknown world and shot the hell out of the aliens. No wonder extra-terrestrials haven’t made contact with us when we make this kind of film about them. Apparently when signals are transmitted from Television Centre to our TV’s they are also sent out into space. We’ve been inadvertently broadcasting re-runs of Aliens, Starship Troopers and Doom into space for (light) years. We’ve also been broadcasting X –Factor and Strictly Come Dancing into space for the last ten years which may be another reason they’ve not made contact.

Literary sci-fi has its fair share of space marines-action-shoot ‘em ups but this is balanced by philosophical, thought provoking concepts. Two of Britain’s biggest selling sci-fi writers are Ian M. Banks (sorely missed) and Alistair Reynolds. Why have they never made any of these great writer’s books into films? Not enough fight scenes perhaps or maybe the media again underestimates the cinema-going public’s grasp of big thought provoking concepts. Some of the best sci-fi has been thought provoking, mind and opinion changing. Take 1984. The phrase Orwellian is now used to describe states such as North Korea. Brave New World is another example and it’s a real shock that no one has tried to put Huxley’s dystopia on the big screen (although there is a TV series from the Seventies). Perhaps, maybe, because the premise is too close to the knuckle; a society patronised by its leaders and the media, continually told to be happy and smile and not think too much. Oh, while you’re up, pass me the Soma would you?

So imagine if Winston Smith and Julia had been lying together in that rented room above the junk shop in the East end of London in Oceania. As they talk, asking each other if they are the dead a voice booms from the telescreen concealed behind the picture.

‘You are the dead! Make no move, remain exactly where you are…’

As the thought police smash their way in Winston, still naked, grabs two massive lazer guns from under the bed supplied by the Brotherhood.

‘No way, mutherfuckers, you are the dead!’

As he opens fire on the thought police Julia produces a bomb.

‘What, you’re part of the resistance too?’ gasps Winston between firing off lazer rounds.

‘I’m sorry I couldn’t tell you Winston, I had to protect you.’

‘Yeah? Well the revolution begins here baby. Let’s show these Ministry of Love bastards some real thought crime. Hey, big Brother, Eat this!!!!!’

Winston shots a helicopter out of the sky with the atomic grenade launcher, then grabs Julia’s hand and they bolt out of the shop taking out that ministry agent, the shop owner, before they by smashing his head into the telescreen by the front door.

Jason Statham would play Winston Smith and it would be in a cinema near you.

this originally appeared on Paul's website at http://paulmelhuish.wordpress.com

All brilliant but then the fighting began. I sat through repeated action sequence after action sequence and this caused me to wonder if all these sequences were specifically put in to keep the audience happy.

So, what do I mean by keeping the audience happy? I’m not saying that Britain is populated by knuckle dragging morons who’s attention is only kept by action sequences and let me categorically state that I DO NOT BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE. You cannot separate our society into two fractions; those who watch documentaries on BBC4 and those who watch the X Factor. I don’t believe humanity cannot be so easily categorised. I have friends who don’t have a humanities degree and like to watch the X Factor but also understand the complex metaphysical conundra central to the plot on a programme such as Life on Mars. They understand it but don’t use pretentious phrases such as ‘metaphysical conundra’ to explain it like just did.

From my perspective that film producers seem to think that you can categorise society like this and an action sequence will bring in the masses of drooling Burberry-wearing chavs to a film like Elysium because they won’t understand the plot and a fight sequence will keep them entertained. The media always underestimates the intelligence of the average citizen.

Sci-fi, in the cinema at least, now seems to equate lots of shooting with big, futuristic looking guns. Since the space-marines in Aliens stepped out onto LV-426 back in 1987 there has followed a trail of films where space marines step onto an unknown world and shot the hell out of the aliens. No wonder extra-terrestrials haven’t made contact with us when we make this kind of film about them. Apparently when signals are transmitted from Television Centre to our TV’s they are also sent out into space. We’ve been inadvertently broadcasting re-runs of Aliens, Starship Troopers and Doom into space for (light) years. We’ve also been broadcasting X –Factor and Strictly Come Dancing into space for the last ten years which may be another reason they’ve not made contact.

Literary sci-fi has its fair share of space marines-action-shoot ‘em ups but this is balanced by philosophical, thought provoking concepts. Two of Britain’s biggest selling sci-fi writers are Ian M. Banks (sorely missed) and Alistair Reynolds. Why have they never made any of these great writer’s books into films? Not enough fight scenes perhaps or maybe the media again underestimates the cinema-going public’s grasp of big thought provoking concepts. Some of the best sci-fi has been thought provoking, mind and opinion changing. Take 1984. The phrase Orwellian is now used to describe states such as North Korea. Brave New World is another example and it’s a real shock that no one has tried to put Huxley’s dystopia on the big screen (although there is a TV series from the Seventies). Perhaps, maybe, because the premise is too close to the knuckle; a society patronised by its leaders and the media, continually told to be happy and smile and not think too much. Oh, while you’re up, pass me the Soma would you?

So imagine if Winston Smith and Julia had been lying together in that rented room above the junk shop in the East end of London in Oceania. As they talk, asking each other if they are the dead a voice booms from the telescreen concealed behind the picture.

‘You are the dead! Make no move, remain exactly where you are…’

As the thought police smash their way in Winston, still naked, grabs two massive lazer guns from under the bed supplied by the Brotherhood.

‘No way, mutherfuckers, you are the dead!’

As he opens fire on the thought police Julia produces a bomb.

‘What, you’re part of the resistance too?’ gasps Winston between firing off lazer rounds.

‘I’m sorry I couldn’t tell you Winston, I had to protect you.’

‘Yeah? Well the revolution begins here baby. Let’s show these Ministry of Love bastards some real thought crime. Hey, big Brother, Eat this!!!!!’

Winston shots a helicopter out of the sky with the atomic grenade launcher, then grabs Julia’s hand and they bolt out of the shop taking out that ministry agent, the shop owner, before they by smashing his head into the telescreen by the front door.

Jason Statham would play Winston Smith and it would be in a cinema near you.

this originally appeared on Paul's website at http://paulmelhuish.wordpress.com

Monday, 11 November 2013

Moon versus Sun, by Ian Watson

This is a retrospective look at Duncan Jones´s much-lauded 2009 film Moon, with a wee bit concerning Danny Boyle´s slightly less lauded 2007 film Sunshine, written with the innocence of ignorance. In other words I´m ignoring all the wealth of background info available to anyone who googles Wiki, and just going on my original first impressions.

In Moon, Earth is dependent for its power resources on Helium-3 scraped off the surface of our satellite by big mining machines (vaguely plausible) and sent to Earth in space torpedos. Supervising all of this lunar activity is precisely one chap called Sam who lives in something the size of a modest shopping mall, under the illusion that he’s on a short-term contract. (There’s another nifty mall in the Dr Who Waters of Mars episode: enormous empty pressurised spaces for running through in panic, that must weigh hundreds of tons, although allegedly cargo space on the Mars-bound spaceship was so limited that they couldn’t even take a bicycle with them to cover the unnecessary distances from A to B and C and D and E.)

Sam non-communicates with his loving wife back home by recorded videos – none of that one-and-a-half second delay real-time communication nonsense such as has been popular since Apollo first landed.

As a companion in his solitude Sam has a clunky mobile Cyclops-eyed Artificial Stupidity which often advises him to visit the infirmary. (Cue Hal from 2001: I–do–not-recommend-that, Sam…) For lo, unbeknownst to Sam, he is a clone with implanted false memories à la Phil Dick (think Total Recall); and his body will fall apart before too long – whereupon another clone will be awoken from the many in storage in the off-limits basement of the mall.

Evidently nobody in their right mind would ever wish, for scientific or any other reasons, to be paid to live on the Moon in a luxurious mall (especially when the mall benefits from normal Earth gravity, unlike outside where you need to move in lunar slow motion). No, obviously you’d supervise Earth’s vital energy supply by using up, one by one, solitary clones that fall apart. Cloning technology and cryo-storage of umpteen spares is so economical.

When Sam has an accident outside, the Artificial Stupidity mistakenly thinks he’s defunct and awakens another Sam, which leads to poignant Solaris moments of existential bewilderment, while melancholy celestial music à la Gattica plays at great length to establish a philosophical mood. After a bit of a stand-off, Sam and Sam start playing ping-pong, which justifies the mall already being provided with a ping-pong table which usually requires a player at each end.

A discovery! The torpedo which would supposedly send a Sam back to Earth after his stint is actually a highly efficient incinerator; there’s just a tiny trace of ash on the floor, which the Artificial Stupidity failed to completely vacuum up.

Moon so tries to be stylish and cool, but the problem is that the story is deeply silly. Viewing the film as an unintentional farce from the outset will enhance one’s experience quite a bit. I recommend Moon parties with a prize for the funniest catcalls.

Sunshine has a slightly dodgy idea too, namely that you can rekindle a dimmed sun by chucking a lot of our world´s fissile material into our star in the form of a superbomb. I fancy you could toss the entire Earth into the sun without making much flicker of a difference to solar output, but never mind that. Sunshine is so stylish and hot, as well as cool, that this doesn´t matter a hoot. Without going into details, since I don´t have enough time today (rather as Fermat scribbled in a margin that was too narrow for his Last Theorem) and since I feel metaphorical rather than analytical, Sunshine pushes all my buttons of, ahem, illumination. Emotional and dramatic and visual insight, rather than dimness, especially of wits.

(c) Ian Watson 2013

This originally appeared on The Ultimate Adventure Magazine website

In Moon, Earth is dependent for its power resources on Helium-3 scraped off the surface of our satellite by big mining machines (vaguely plausible) and sent to Earth in space torpedos. Supervising all of this lunar activity is precisely one chap called Sam who lives in something the size of a modest shopping mall, under the illusion that he’s on a short-term contract. (There’s another nifty mall in the Dr Who Waters of Mars episode: enormous empty pressurised spaces for running through in panic, that must weigh hundreds of tons, although allegedly cargo space on the Mars-bound spaceship was so limited that they couldn’t even take a bicycle with them to cover the unnecessary distances from A to B and C and D and E.)

Sam non-communicates with his loving wife back home by recorded videos – none of that one-and-a-half second delay real-time communication nonsense such as has been popular since Apollo first landed.

As a companion in his solitude Sam has a clunky mobile Cyclops-eyed Artificial Stupidity which often advises him to visit the infirmary. (Cue Hal from 2001: I–do–not-recommend-that, Sam…) For lo, unbeknownst to Sam, he is a clone with implanted false memories à la Phil Dick (think Total Recall); and his body will fall apart before too long – whereupon another clone will be awoken from the many in storage in the off-limits basement of the mall.

Evidently nobody in their right mind would ever wish, for scientific or any other reasons, to be paid to live on the Moon in a luxurious mall (especially when the mall benefits from normal Earth gravity, unlike outside where you need to move in lunar slow motion). No, obviously you’d supervise Earth’s vital energy supply by using up, one by one, solitary clones that fall apart. Cloning technology and cryo-storage of umpteen spares is so economical.

When Sam has an accident outside, the Artificial Stupidity mistakenly thinks he’s defunct and awakens another Sam, which leads to poignant Solaris moments of existential bewilderment, while melancholy celestial music à la Gattica plays at great length to establish a philosophical mood. After a bit of a stand-off, Sam and Sam start playing ping-pong, which justifies the mall already being provided with a ping-pong table which usually requires a player at each end.

A discovery! The torpedo which would supposedly send a Sam back to Earth after his stint is actually a highly efficient incinerator; there’s just a tiny trace of ash on the floor, which the Artificial Stupidity failed to completely vacuum up.

Moon so tries to be stylish and cool, but the problem is that the story is deeply silly. Viewing the film as an unintentional farce from the outset will enhance one’s experience quite a bit. I recommend Moon parties with a prize for the funniest catcalls.

Sunshine has a slightly dodgy idea too, namely that you can rekindle a dimmed sun by chucking a lot of our world´s fissile material into our star in the form of a superbomb. I fancy you could toss the entire Earth into the sun without making much flicker of a difference to solar output, but never mind that. Sunshine is so stylish and hot, as well as cool, that this doesn´t matter a hoot. Without going into details, since I don´t have enough time today (rather as Fermat scribbled in a margin that was too narrow for his Last Theorem) and since I feel metaphorical rather than analytical, Sunshine pushes all my buttons of, ahem, illumination. Emotional and dramatic and visual insight, rather than dimness, especially of wits.

(c) Ian Watson 2013

This originally appeared on The Ultimate Adventure Magazine website

Monday, 4 November 2013

Old Enough to Know Better but too Dumb to Care, an article by Rod Rees

NSFWG member Rod Rees on becoming a writer...

I’m thinking of declaring a jihad against actuaries.

Bastards.

My theory is that they’re in league with the

government to stop me retiring. I’m getting to feel like Tantalus: every time

the fruits of a pension come within reach they change the pensionable age and

I’m back to square one looking for something to do that will provide me with

three square a day.

And then, of course, when you could actually use an

actuary – professionally rather than for fertiliser that is – there’s nary one

of the buggers around. And, boy, the day I decided it would be a good idea to

write a novel was sure as hell one when I could have used some advice of a

statistical nature.

Gotta tell you, if deciding to write a novel is a

dumb idea, then deciding to write one when you’re at the wrong end of your

fifties is a really dumb idea.

Fifty is a funny age. It’s the Wednesday of your

lifetime: too far from the fun-packed weekend of your youth and too far from

payday ever to stand a chance. It’s the age – as Leonard Cohen so pithily

reminds us – when we begin to ache in the places where we used to play. It most

certainly is not an age to embark on novel writing. But then I suppose there’s

no good age to start writing because it is – both actually and actuarially – a

stupid occupation.

Okay, you need to be stupid to start writing a book.

But read any guide to ‘writing a book’ and the word ‘determination’ features

prominently, this being the trait considered necessary to finish writing a book. But in my case you can substitute

‘determination’ for ‘enraged naivety’. I was prompted to write ‘Dark

Charismatic’ after watching the travesty of a re-imagining of the Jekyll and

Hyde story that was the BBC’s ‘Jekyll’. Now although I love and revere Stevenson’s

tale I nevertheless accept that like many things approaching their one hundred

and twenty-fifth birthday (me, for example) it could certainly handle a wash

and brush up. Unfortunately as wash and brush ups go the BBC’s effort was more

akin to a really good sand blasting in that it stripped all the good things

away and left ... well, not much actually. And like many before me, as I sat

there aghast watching this twaddle, the thought crossed my mind, ‘I could do

better than that’.

Fool! Such hubris!

So I sat down and wrote ... and wrote and wrote and

wrote. Two hundred and twenty thousand words to be exact, each word of them

carefully, lovingly and laboriously crafted. And the final two were ‘The End’.

Now here I pause to proffer my first statistic, namely,

the one regarding how many books once commenced are ever completed. My guess –

and I suspect this is an amazingly generous estimate – is that no more than one

in a hundred neophyte writers ever stagger across the finishing line. Around

the country there must be millions of first, second and third chapters

gathering dust in drawers or languishing forgotten on laptops (and long may

they remain there; who needs competition). And as support for this contention I

am willing to bet, dear reader, that you too are the proud possessor of an

unfinished novel.

So remember that statistic: only one in a hundred

books is ever finished.

Having written the bloody thing I was troubled by a

rather belated thought: what do I do with it now? And the answer is, of course,

get an agent. Oh, you can do it yourself, sending your unsolicited manuscript

to publishers directly but you might as well spend your time attempting to

roast snow. Believe me, nobody in the publishing world will touch unsolicited

manuscripts. They’re the tsetse fly of the literary world: everyone’s heard of

them but no one wants to come in contact with them. So I googled ‘agents +

science fiction + fantasy’, chose the three I thought most receptive – that is they

had kind faces – and sent off the first three chapters of my magnum opus. And

waited...and waited...and waited. One outright (or is that outwrite) rejection

in the form of a platitudinous standard letter, one rejection because ‘the end

of the book was obvious’ – the guy must be prescient or something because I

didn’t know what the ending was until a week before I sent it off – and –

hurray! – one acceptance.

So back to those statistics. In later conversation

with my agent (get me: ‘my agent’) he advised me that during his time in the

business he’d received something north of six thousand submissions from

would-be writers and as he’s currently got a stable (or should that be a pen)

of forty-three authors that comes out at a newby having something like one

chance in a hundred and fifty of securing an agent.

Remember that: you’ve one chance in a hundred and

fifty of finding an agent.

So ‘Dark Charismatic’ was sent out ... and every

publisher and his father rejected it. The general feeling was that there was

too much sex in it. My fault: in retrospect what I’d written was an over-long

aide-memoire, something to refer to if Alzheimer’s kicked in and I found myself

with some free time on a Saturday night. So what do I do now? As I’d just spent

a year wasting my time, writing unpublishable crap and earning precisely zip, the

answer was obvious: I’d write another book! I think this sort of behaviour is

classifiable under Obsessive Compulsive Disorders. Anyway, thus was born ‘The

Demi-Monde’. Another year drifted by but this time when my agent pitched the

book it was taken up by a publisher.

Remember that: there’s only one chance in two of your

agent being able to find a publisher for your book.

Okay, so you’ve got a publisher now, so let’s have a

look at the sales prospects for your master work. Somewhere between seventy

thousand new fiction titles hit the bookshelves every year in the UK and the

average sales of each are somewhere between one thousand and three thousand

copies. That’s average, folks, so there are some seriously shit sales needed to

compensate for the stellar success of such luminaries as Dan Brown and Stieg

Larsson. No matter, these average sales, by my calculations, will net the

author between £500 and £1,500. That’s after two years bloody hard work (and

don’t forget you’ll also have to go through the publisher’s editing process

which can be enormously time consuming, especially if your grammar is as rotten

as mine ... or, possibly, mine is): that works out at about 10p an hour.

Minimum wage it ain’t. It makes misdirecting customers at B&Q look like a

gig from heaven.

So what are your chances of your book generating

something approaching a reasonable return on your investment of time – say £30,000

a year? My guess is that maybe two and a half thousand titles turn that sort of

profit for their authors: one in thirty.

Remember that: one book in thirty turns an okay

profit.

If I recall my statistics – and those lectures were a

bloody long time ago – the chance of you finishing a book, finding an agent,

having it published and turning a reasonable profit is about one in forty

thousand. Or about the same chance you run of being struck by a renegade meteor

... on a Sunday ... in Slough.

That’s why, in my humble opinion, the chief quality

needed by a would-be writer isn’t determination, or creativity, or style, or a

wonderful plot idea ... it’s stupidity. No matter how you slice it, writing’s a

mug’s game.

But to paraphrase Lloyd in ‘Dumb and Dumber’: ‘One

chance in forty thousand? So you’re telling me I’ve got a chance’.

What do actuaries know anyway?

Monday, 28 October 2013

Hollywood Halloween news from Ian Watson...

Sci-Fi Film To Be Put On Ice?

Steve Spellborg’s proposed sci-fi movie The Silent Ones, due to feature hundreds of Emperor Penguins awaiting the return to Earth of superscience birdlike aliens, has enraged environmentalists.

Crowds of Emperors, the tallest of penguins, stand motionless on the ice for several months during the snowstorms of the Antarctic winter while incubating their eggs with their feet. In Spellborg’s story they’re all standing expecting something – the return of a mother ship, which duly arrives, and on to which they all will waddle, rather as in his 1981 blockbuster Abductions of the Third Sort. In The Silent Ones an obsessed ornithologist, haunted by dreams, will battle his way to the frozen south with his ufologist girlfriend.

An Emperor Penguin yesterday, without his egg...

Conservationists protest that all the light and heat produced by the film crews may poach the penguins’ eggs, or make those hatch prematurely, and fear that the puzzled penguins might become psychotic.

In a press statement released yesterday at 6.30 pm Hollywood time, Spellborg declared his determination to commence location shooting by Christmas, and insisted that no penguins, nor their eggs, will be harmed physically nor psychologically during the making of The Silent Ones. To minimise disturbance and ecological impact, the living quarters of the location film crew will be in a nuclear submarine which the US navy has now pledged to put at his disposal, and which will stay submerged as much as possible.

Monday, 21 October 2013

"I like to, uh, you know, edit...", an article by Mark West

NSFWG member Mark West on editing. The chapbook story mentioned, "What Gets Left Behind", was critiqued by the group during the summer of 2011 and published in 2012

You know how, sometimes, you enjoy an activity that’s a little bit uncool - or disliked by others - and although you maintain your love of it, it’s always under a cloak of secrecy? Well rather than stand there, hands in pockets and a tinge of blush in my cheeks, I’ll stand proud and say it loud - I like editing.

There, I’ve said it. Admittedly, half the people who started reading this have now gone off to do something a little more exciting instead, but for those who are left - thank you - bear with me.

According to Stephen King’s brilliant (and, I’d say, fairly essential) memoir of the craft, “On Writing”, there are two types of writer - the ‘taker-out’ and the ‘putter-in’ - and all of us, broadly, fall into one of those camps. My friend Gary McMahon is a ‘putter-in’ and his early drafts are astonishingly concise - by comparison, even I struggle to get through a reading of my first draft. In fact, it’s become a matter of absurd pride to me that nobody else has ever read one of my first drafts - I tried it once, about fifteen years ago and I’m still waiting for the feedback. My first draft is the dumping ground, the place where everything I know about the story comes out (and I often have to write things I know won’t survive the draft, just so I can completely understand the characters journey from point A to point B). That works for me, because when I go back to the second draft, I have plenty of material to work on. It also means I cut a lot out - my novel “In The Rain With The Dead”, for instance, was 126,000 words in first draft and published as 104,000 words.

Editing is essential, as important a part of the process as coming up with the idea and the act of committing it to paper. In fact, if you want a timeline, it’s - think of a story, write the story, edit the crap out of it. Editing is where you refine what you have in your head, where you refine that personal and original vision into prose that’s tight and concise enough for everyone else to see that same vision.

What’s also important to remember is that not every writer makes a good editor. Yes, most of us can pick up some grammatical errors or punctuation problems but hey, if you’re like me and have an occasional issue with apostrophes, if you got it wrong the first time, you’ll probably get it wrong when you redraft too. So here’s my advice - get some readers in. I tend to call my happy little band “pre-readers”, but I’ve seen them referred to as ‘beta-readers’ too - it doesn’t matter what name they go under, get them. And audition them too because a reader who loves everything a writer puts out isn’t any use in the editing process at all.

I’ve been very lucky, to build up a steady band of pre-readers over the years. I have my kid sister (and boy, is she a tough crowd to please!), a few non-writer friends (one works in medicine and puts me right on matters of grue and gore, whilst another is scathing even about stuff he likes), a handful of writers for the technical side of things and my wife, who looks at the whole package. I’m also lucky enough to belong to an excellent writing group - Northampton SF Writers - and they are very thorough. For individual projects, I might draft other people in, but the core remains the same. And what purpose do they serve? They read what I consider to be an edited draft and then have at it - does it work for them, does the language flow, do the set-pieces work, do characters name or attributes change (as can happen), is it believable (story AND character) and, most important of all, did they enjoy it? I take in their comments and read all of them, even if I end up ignoring perhaps 50% of them. I’ll make changes where I can plainly see I’m wrong or, if they all say something is rubbish and I disagree, I’ll make the change and see how it works for myself. Then I’ll move onto the next draft and get that pre-read too (though by a smaller crowd this time - strangely, for some people, one run is enough).

The key thing is, the pool of writers grows larger every day, the call to the buying public gets louder every day and you need to stand out from that throng. One way is to have a story as tight as you can possibly get it.

With electronic publishing now a viable means for just about anybody with Word and Internet access, editing is more important than ever. Some people reading this will remember the PublishAmerica business, around 2000/2001, where there suddenly seemed to be thousands of horror novels being published, most with dreadfully designed covers and poor use of fonts, all of them proclaiming themselves the next big thing in horror. In my experience - yes, I read some - the covers weren’t the worst of it and the closest they got to horror was that they were nigh on unreadable. The same, if it isn’t already (thinking of that lady who wrote “The Greek Seaman”), is undoubtedly going to be true of Smashwords and Kindle.

Horror is an odd genre, in a lot of ways. I love it, because it’s rich and varied and covers the spectrum of human experience. Others love it because when it hits, it hits big. Think of the paperback horror boom in the 80s, when anything with a skeleton on a black cover could get published. Was it quality stuff? No, of course it wasn’t and the poor quality of it helped to sour readers on the genre. I think that happened with the PublishAmerica issue - people bought the next big things in horror only to discover that they were poorly written, sloppily edited rubbish. So what happens then? That’s right, another bust for the genre as consumers are fearful of taking a chance on new horror, in fear that “its like wot tht idiot writ”.

As an example (and breaking my cardinal rule), here’s a comparison between the first draft of "What Gets Left Behind" (my Spectral Press chapbook) and the third:

1st draft

The summer holidays were already underway and, for Mike and his best friend Geoff, the endless sunny days lay ahead of them like uncharted waters, holding promise of adventure and fun. Having been to see “Raiders of The Lost Ark” at the old ABC in town earlier in the month, on their own, had only fuelled their imagination. Mike now owned a brown fedora hat his uncle had picked up for him from Heyton, though he’d had to take off the ‘Kiss Me Quick’ band from around it.

It’s not bad, is it? It wouldn’t win any prizes, but it gets the point across and there’s a nice little bit of nostalgia in there. But how does it affect the story? Does it slow it down, does it branch off, is it necessary?

3rd draft

The summer holidays were already underway and, for Mike and his best friend Geoff, the endless days lay ahead of them like uncharted water, promising adventure and fun. Having seen “Raiders Of The Lost Ark” at the old ABC earlier in the month only fuelled their imaginations.

The thrust is still there, but you read it and go - you know the kids are on holiday, that they’re looking for adventure and that Indiana Jones is going to be a factor. That’s all you need to know.

The best editing in the world won’t make up for poor writing, but good editing and good writing can combine to make your story much more powerful. Maybe powerful enough for the casual reader to think ‘Hey, I liked that, I wonder if he has anything else out?’

Edit, people, it’s what makes your words make sense.

This originally appeared on Steve Lockley's Confessions of a technophobe website, as part of a series on writing tips from various authors, in June 2011.

You know how, sometimes, you enjoy an activity that’s a little bit uncool - or disliked by others - and although you maintain your love of it, it’s always under a cloak of secrecy? Well rather than stand there, hands in pockets and a tinge of blush in my cheeks, I’ll stand proud and say it loud - I like editing.

There, I’ve said it. Admittedly, half the people who started reading this have now gone off to do something a little more exciting instead, but for those who are left - thank you - bear with me.

According to Stephen King’s brilliant (and, I’d say, fairly essential) memoir of the craft, “On Writing”, there are two types of writer - the ‘taker-out’ and the ‘putter-in’ - and all of us, broadly, fall into one of those camps. My friend Gary McMahon is a ‘putter-in’ and his early drafts are astonishingly concise - by comparison, even I struggle to get through a reading of my first draft. In fact, it’s become a matter of absurd pride to me that nobody else has ever read one of my first drafts - I tried it once, about fifteen years ago and I’m still waiting for the feedback. My first draft is the dumping ground, the place where everything I know about the story comes out (and I often have to write things I know won’t survive the draft, just so I can completely understand the characters journey from point A to point B). That works for me, because when I go back to the second draft, I have plenty of material to work on. It also means I cut a lot out - my novel “In The Rain With The Dead”, for instance, was 126,000 words in first draft and published as 104,000 words.

Editing is essential, as important a part of the process as coming up with the idea and the act of committing it to paper. In fact, if you want a timeline, it’s - think of a story, write the story, edit the crap out of it. Editing is where you refine what you have in your head, where you refine that personal and original vision into prose that’s tight and concise enough for everyone else to see that same vision.

What’s also important to remember is that not every writer makes a good editor. Yes, most of us can pick up some grammatical errors or punctuation problems but hey, if you’re like me and have an occasional issue with apostrophes, if you got it wrong the first time, you’ll probably get it wrong when you redraft too. So here’s my advice - get some readers in. I tend to call my happy little band “pre-readers”, but I’ve seen them referred to as ‘beta-readers’ too - it doesn’t matter what name they go under, get them. And audition them too because a reader who loves everything a writer puts out isn’t any use in the editing process at all.

I’ve been very lucky, to build up a steady band of pre-readers over the years. I have my kid sister (and boy, is she a tough crowd to please!), a few non-writer friends (one works in medicine and puts me right on matters of grue and gore, whilst another is scathing even about stuff he likes), a handful of writers for the technical side of things and my wife, who looks at the whole package. I’m also lucky enough to belong to an excellent writing group - Northampton SF Writers - and they are very thorough. For individual projects, I might draft other people in, but the core remains the same. And what purpose do they serve? They read what I consider to be an edited draft and then have at it - does it work for them, does the language flow, do the set-pieces work, do characters name or attributes change (as can happen), is it believable (story AND character) and, most important of all, did they enjoy it? I take in their comments and read all of them, even if I end up ignoring perhaps 50% of them. I’ll make changes where I can plainly see I’m wrong or, if they all say something is rubbish and I disagree, I’ll make the change and see how it works for myself. Then I’ll move onto the next draft and get that pre-read too (though by a smaller crowd this time - strangely, for some people, one run is enough).

The key thing is, the pool of writers grows larger every day, the call to the buying public gets louder every day and you need to stand out from that throng. One way is to have a story as tight as you can possibly get it.

With electronic publishing now a viable means for just about anybody with Word and Internet access, editing is more important than ever. Some people reading this will remember the PublishAmerica business, around 2000/2001, where there suddenly seemed to be thousands of horror novels being published, most with dreadfully designed covers and poor use of fonts, all of them proclaiming themselves the next big thing in horror. In my experience - yes, I read some - the covers weren’t the worst of it and the closest they got to horror was that they were nigh on unreadable. The same, if it isn’t already (thinking of that lady who wrote “The Greek Seaman”), is undoubtedly going to be true of Smashwords and Kindle.

Horror is an odd genre, in a lot of ways. I love it, because it’s rich and varied and covers the spectrum of human experience. Others love it because when it hits, it hits big. Think of the paperback horror boom in the 80s, when anything with a skeleton on a black cover could get published. Was it quality stuff? No, of course it wasn’t and the poor quality of it helped to sour readers on the genre. I think that happened with the PublishAmerica issue - people bought the next big things in horror only to discover that they were poorly written, sloppily edited rubbish. So what happens then? That’s right, another bust for the genre as consumers are fearful of taking a chance on new horror, in fear that “its like wot tht idiot writ”.

As an example (and breaking my cardinal rule), here’s a comparison between the first draft of "What Gets Left Behind" (my Spectral Press chapbook) and the third:

1st draft

The summer holidays were already underway and, for Mike and his best friend Geoff, the endless sunny days lay ahead of them like uncharted waters, holding promise of adventure and fun. Having been to see “Raiders of The Lost Ark” at the old ABC in town earlier in the month, on their own, had only fuelled their imagination. Mike now owned a brown fedora hat his uncle had picked up for him from Heyton, though he’d had to take off the ‘Kiss Me Quick’ band from around it.

It’s not bad, is it? It wouldn’t win any prizes, but it gets the point across and there’s a nice little bit of nostalgia in there. But how does it affect the story? Does it slow it down, does it branch off, is it necessary?

3rd draft

The summer holidays were already underway and, for Mike and his best friend Geoff, the endless days lay ahead of them like uncharted water, promising adventure and fun. Having seen “Raiders Of The Lost Ark” at the old ABC earlier in the month only fuelled their imaginations.

The thrust is still there, but you read it and go - you know the kids are on holiday, that they’re looking for adventure and that Indiana Jones is going to be a factor. That’s all you need to know.

The best editing in the world won’t make up for poor writing, but good editing and good writing can combine to make your story much more powerful. Maybe powerful enough for the casual reader to think ‘Hey, I liked that, I wonder if he has anything else out?’

Edit, people, it’s what makes your words make sense.

This originally appeared on Steve Lockley's Confessions of a technophobe website, as part of a series on writing tips from various authors, in June 2011.

Monday, 14 October 2013

Kubricked, an article by Ian Watson

Emilio d’Alessandro, Christiane Kubrick, and Ian

at the Festival Internazionale della Fantascienza in Trieste, September 2001

Early in 1990, the phone rang. Stanley Kubrick’s assistant asked me to visit

the film-maker at his home near St Albans.

Why could not be disclosed.

A chauffeur would come. I must

read material sent by motorbike courier.

I’d heard

rumours of a project for a film about a robot boy. Due to the secrecy, and a sense of entering a

lion’s den, I opted to drive my own car.

Stanley lived in

enigmatic seclusion for years near St Albans, nowhere near Hollywood. Actually, he wasn’t at all the misanthropic

hermit portrayed by journalists peeved at being unable to report much about

him. He was a devoted husband and

father, and constantly companionable by phone with people worldwide. But he was very focused on his

art.

My

memory of that first meeting with Stanley fades into umpteen subsequent

meetings, but the impression which abides (since Stanley’s appearance never

changed) was of a quizzical scruffy figure, bespectacled eyelids hooded,

receding hair and beard untidy, dressed in baggy trousers, a jacket with lots

of pockets and pens, and tatty old trainers – along with a quirky amiable dry

humour and an intensity of focus which could jump disconcertingly from one

topic to another far remote.

I never mastered

the lay-out of the manor house, but its labyrinth included a mini-movie theatre

where Stanley could study the latest screen releases, a sepulchral computer

room where two cats who never saw the light of day glided like wraiths, a

billiard room where Stanley and I were to sit brainstorming for untold hours --

and a huge cheery kitchen where I would share lunches with Stanley. Gorgeous floral paintings by Stanley’s wife

Christiana brightened walls.

Lunches remained

exactly the same for weeks, since if Stanley liked something he persisted with

it until he tired. First, were Chinese take-aways ferried in by

Stanley’s chauffeur Emilio. Next,

vegetarian cooks were hired, till they proved not to be true vegetarians. Finally, Stanley would poach salmon in the

microwave, a skill of which he was proud.

Stanley gave me

a book about artificial intelligence and a copy of Pinocchio, the tale

of the puppet who yearned to be a real boy.

The movie he planned was to be a futuristic fairy-tale robot version,

spinning off from a vignette by Brian Aldiss, but the plot-line had bogged

down. Would I write a 12,000 word story,

doing whatever I wished with the material?

Three weeks

later I mailed the result, and Stanley wanted to meet me again. Any illusion that I’d created a usable

story-line evaporated fast. My story was

no use for the project – bye-bye story,

never to see the light of day – but Stanley liked the way I’d gone about

writing it. Would I work with him on a

week-by-week basis?

For almost a

year I was to be Stanley’s mind-slave, writing scenes in the morning to fax

around noon for long discussion by phone in the evening, or being collected by

Emilio to arrive for lunch and an afternoon of mental gymnastics. A sign on a wall nearby said: Here we

snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

Stanley

initially asked whether alcohol would hamper my performance, but I assured him

that beer was necessary to my thought processes. So a hospitable crackle would come over the

short-wave radio: “Bucket of beer for Ian!”

In the big manor house,

communications with Stanley were often by radio. One day I’d been nattering to Stanley’s

assistants Tony and Leon for almost an hour when Stanley walked in and

glared. “You’re supposed to tell me when

Ian gets here.” “Your radio isn’t

switched on, Stanley…” they replied.

Perfect organisation could sometimes break down.

Even ordinary

conversations with Stanley could be disconcerting since he would suddenly shift

to an entirely different theme, as if he’d lost interest in what was of

consuming interest a moment earlier.

When we were discussing the story line, these veerings became

extreme. What if our robot boy`s teddy

bear has a kangaroo pouch to keep things in?

Next moment: will the next government

introduce currency controls immediately they gain power? After a spot of politics, back to our story:

how about a café where robots hang out, pretending to drink?

I decided that

Stanley’s intention, whether deliberate or instinctive, was to maintain mental

intensity hour after hour, never mind how exhausting this might be – a way of

sustaining and heightening my performance, and his own too perhaps, which has

left some people who worked with him feeling drained dry. What he wanted, he didn’t exactly know. It was up to me as soothsayer to guess. Yet he was remoselessly logical in finding

loopholes in lovely proposed scenes, little hair-cracks which could rapidly

widen into uncrossable chasms.

Story

conferences were like building houses of cards, often doomed to collapse just

when I was hoping to leave with scribbled notes to turn into scenes. Stanley Kubrick only wanted the absolute best

– for the story, or for the resident cats and dogs; and plugging away at

something about which he had an instinct must eventually bear

fruit. Was it 58 times that Stanley

reshot Jack Nicholson crossing a street in The Shining in the hope, as

Stanley told me, that something interesting would happen?

Early on I’d

established a protective cordon by telling Stanley that I would only work

weekdays. When one plot mishap escalated

into a catastrophe, Stanley eyed me gravely.

“There’s a lot of money in this for you, Ian” – referring to the

pie-in-the-sky bonus. Distraught at the

suggestion that I might work all weekend or not go to bed, I retorted, “There’s

no point in threatening me with money.

I’m not mainly motivated by it.” Stanley gaped at me in

bewilderment. By five in the afternoon,

we could both be fairly wiped out. We

shambled towards an editing suite, where Stanley stared blankly at his aide,

Leon. “Do you know where Leon is?” he

asked. “I am Leon,” said

Leon.

As a model for how robots should talk, I must

watch Peter Sellers as the retarded gardener in Being There. I faxed: “You are beautiful. I have a clean dick.” (“That’s more like it,” Stanley told

me.) “You are a goddess. May I sit in your car?” Stanley would instruct me to “Stop writing

dialogue! Just describe it!” Then change his mind: “No, write it all in

dialogue!” I was beginning to feel like

a deranged robot myself. A Robo-Scribe,

with contradictory programs.

It was as if

each morning I started writing an entirely new short story which I was soon

forced to abandon, only to begin another story next day. This could be irksome for an author, though

as Stanley said to me when I tried to defend a scene, “The trouble with you

writers is you think your words are immortal.”

On the inside of the manor house door was a notice: DO NOT LET DOGS

OUT. As I prepared to depart one day,

Stanley paused by the notice and growled, “It should say writers too.”

While filming Eyes

Wide Shut, after the umpteenth take of a scene, Stanley said deadpan to a

frazzled Tom Cruise at the height of his career, “Don’t worry, I’ll make a star

of you yet.” In a similar way, Stanley

seemed determined to make a writer of me yet!

Stanley adopted the role of mentor with Tom Cruise – whose marriage

broke up not long after Stanley filmed him repeatedly simulating sex with his

wife Nicole Kidman – although we should not speak of cause and effect! What was happening to me was a prolonged

master class in the construction of a story.

Stanley Kubrick

hated coincidences in a story. In fact, real life is full of bizarre

coincidences. Spanish friends were once

driving me to Málaga. The motorway was

very foggy. “You can go a bit

faster,” I encouraged. “Nothing can come

in this direction. Unless,” I added

merrily, “there’s an elephant on the road.”

“No elephants in Spain since Hannibal!” said the driver. Nearer to Málaga suddenly the fog cleared,

and in a field beside the motorway stood… an elephant. Did it belong to a circus…? You can’t put

such things into a story because they’d be unbelievable. Fiction needs to be more logical than real

life.

Kubrick`s

long-suffering, loyal chauffeur Emilio’s

dearest wish was to retire to his vineyard south of Monte Cassino. He’d kept practical matters ticking over at

the manor house for ages. When you’re

invaluable to Stanley it’s difficult to escape or to have a life. Emilio did give notice. Three years’ notice, so Stanley could

replace him. Of course Stanley

completely ignored this.

Emilio

and I got on well together so I started learning Italian. “Stanley è nostro zio,” we would

chorus: Stanley is our uncle. It was

Emilio who explained how Stanley could always be wearing exactly the same

clothes, which whilst rumpled had not become filthy. When Stanley found something he liked, he

bought many spares. He wasn’t dressed in

the same jacket and trousers but in duplicates all in much the same state.

Originally

Emilio drove Stanley in a Mercedes with a sunshine roof. During the filming of The Shining

Stanley’s favourite food for several weeks on end had been Big Macs. Finishing one of these in the car while

Emilio was chauffeuring him, Stanley crumpled up the rubbish, spied the open

sunshine roof, and threw the wrappings out.

The wind promptly tossed them back in, all over him. “Fuck,” said Stanley, “this car isn’t much

good.”

A

joke – but could it be that Stanley had become slightly detached from

reality? When Emilio was driving him to

a computer fair in London, Stanley became puzzled. “Why are there all these cars on the road?” “Because people go to work, Stanley.” “Why don’t they work at home?” “Why are you in a car, Stanley?”

Stanley

loved acquiring things. “Do you know

what the essence of movie-making is?” Stanley asked me. “It’s buying lots of things.” One day I arrived with a canvas bag,

essential to transport the increasing bulk of mutually contradictory

printouts. Stanley admired the bag,

which came free with a bottle of French aftershave which I hadn’t wanted. “That is a very good bag, Ian.” “Well, you can’t have it,” I told him, “unless

you buy a bottle of aftershave.”

Promptly he picked up a phone. “Tony,

call Boots in St Albans…” Two bottles of

aftershave and two bags remained in stock.

“Tony, drive into St Albans and get both now.” Not long after, Tony delivered the goods to

our story conference. Happily Stanley

ripped the cellophane off one bag, and patted it. Two months later bottles and bags were still

in the same place on the carpet.

When Full

Metal Jacket was being filmed in England a whole plastic replica Vietnamese

jungle was air-freighted in from California.

Next morning Stanley walked on set, took one look at it, and said, “I

don’t like it. Get rid of it.” The technicians shared out the trees, giving

a new look to gardens in North London, and a real jungle was delivered

instead, palm trees uprooted from Spain.

What

seemed to me caprice was perhaps perfectionism, the exploring of every possible

avenue. “We need some sort of weird

landscape for this story.” “How about

surreal, like Max Ernst?” I asked.

Immediately Tony was sent to Charing Cross Road to buy every available

volume about Max Ernst. Taking the pile

home with me, I wrote surrealistically and faxed off the result. “It’s just a woman in a flowerpot,” sighed

Stanley. “Forget it.”

October

arrived. We were sitting in the kitchen,

door open to the sunlit patio, when I spied a bee on the floor. “There’s a bee on the floor,” I pointed

out. “Will it sting me?” Stanley asked

immediately. Mortality worried him,

which is why he would never fly in a plane, although he had qualified for a

pilot’s licence, which convinced him how dangerous flying is. I rose to inspect the bee – it looked worn

out. “Don’t kill it, Ian! Sit down!”

I’d no intention of killing the poor bee. Bravely Stanley said, “I’ll put it

outside.” So he found a crystal dome and

some stiff card and manouevered the bee under the glass. “You stay here,” he ordered, in case I might

sneak after him, intent on assassinating the bee. Presently he returned proudly from the herb

garden. “I found a place for it.”

A

mischievous imp prompted me. “You know,” I said, “the nights are frosty.” “Do you mean you think the bee might die?” “It might, Stanley, outside.” “Now you’ve made me guilty.” Back into the garden he headed, while I got

on watching CNN. Many minutes passed

till he reappeared, bee under glass once more.

“What do suppose bees eat?” “I

think maybe honey,” I suggested.

So we raided the larder for a big pot of honey, and he spooned out a

volcano-like mound next to the bee. Then

we explored unused rooms of the house for a safe place throughout the coming

winter. Only once this was sorted out

could we tackle the problems of the little lost robot-boy and his teddy bear companion.

Demands for

story conferences escalated. Twice a

week, fine. Three times, well okay. Four times a week was definitely disruptive

and mental turmoil caught up with me.

Given free rein, Stanley would be ever more demanding till you could

become a drained husk. I would be

completed Kubricked, and that wouldn’t help the story. I would become like the writer in The

Shining, dementedly typing All

work and no play makes Jack a dull boy over and over, only in my case

the words would be teddy bear and robot boy.

“Ian,” said

Emilio, “you have to be firm.” So I refused a story conference. When next I turned up, Stanley said

plaintively, “I thought you liked coming down here.” “I do,” I said, “I just need to get my confidence back.” “Ian, you are very confident,” responded

Stanley, though I didn’t feel so at the time.

At the end of

the year, Stanley told me to write the whole story up in ninety pages. “I

hope there’s some emotion in it, Ian,” he confided. “Put some vaginal jelly on the words,” a tip

not often entrusted to writers.

Blessedly, the resulting pages made sense.

Alas,

Stanley became despondent; but he did me the kindness of phoning to say so,

unlike his brusque dismissals of previous failed collaborators. I couldn’t have

worked with him for so long if I hadn’t liked him, and I did feel there was a

special relationship, of avuncular mentor and wayward apprentice.

Three months

later, Stanley recovered heart and phoned: “This is one of the world’s great

stories. Will you write a short synopsis

I can show to people?” Maybe his earlier

doldrums were because he had Kubricked himself, rather than me.

The

quest continued…

After Stanley

died of overwork on Eyes Wide Shut, Steven Spielberg made the robot

Pinocchio, entitled A.I. Artificial Intelligence, in the same

way Stanley himself would have made it, as a homage, and using my screen story

and variant scenes I’d written. A.I. was

the fourth-highest earner worldwide in 2001, partly because Japanese housewives went several times to watch my sex

robot Gigolo Joe. But we aren’t

interested in money – it’s getting the story right that counts. Stanley showed me how.

How effective

was Stanley’s mentoring? In 2003 an

American publisher brought out a new novel by me, to which I’d devoted much

care and effort. At one point a

character asks another, “How will I recognize your brother?” The correct answer would be: “You saw

him in the previous chapter, idiot.”

Whoops! I hadn’t noticed, nor did

the editor, nor reviewers nor readers. I

think- I know- Stanley would have spotted this. Nevertheless I do continue to strive for a

watertight story, and in this task Stanley Kubrick is rarely far from my

mind.

The full version of this article can be found at Ian's site here.

This version was originally broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in 2010

(c) Ian Watson 2010, all rights reserved

Monday, 7 October 2013

Utopia vs Dystopia: The SF Writer's Dilemma, an article by Rod Rees

I

was asked to speak at the Zagreb Literary Festival last week and as a result

found myself on a panel discussing the subject ‘New Utopias’.

I

was asked to speak at the Zagreb Literary Festival last week and as a result

found myself on a panel discussing the subject ‘New Utopias’.

I

have to say it was a subject that left me a little flummoxed and the reason was

simple: I had never thought about writing a story that had anything other than

a dystopian setting. Utopias seemed … boring. Sitting in one of Zagreb’s

wonderful open air cafes enjoying a beer and the late summer sunshine I got to

wondering why this should be.

I

suppose the obvious answer is that a dystopia offers much more plot traction

than a utopia – I mean a world where everything is hunky-dory is hardly one to

get the adrenaline pumping – but maybe there’s more to it than that. Maybe

humanity (and despite what they might believe, SF writers are at least part

human) is frightened of utopias, a contrary thought especially when I find

myself living in a world obsessed with global warming, rising sea-levels,

terrorist atrocities, melt-down in the Middle East to name just a few of the

current disasters de jour.

But

this alarmist tendency is in itself odd especially as, since the Second World

War, things have taken a distinct turn for the better: there have been no world

wars (and the casualties sustained in the ‘regional wars’ are as nothing when

contrasted to their pre-war equivalents), the standard of living of most people

has improved beyond recognition (check out India and China as examples of

that), contagious diseases like smallpox and polio have been mastered, and the

world (on balance) is a much more tolerant place free of maniacal dictators.

But pessimism is still rife.

Why?

And

the more I considered this conundrum the more I came back to the idea that

humanity is frightened of living in a perfect world. So what are the

features of a utopia that frighten people? These are my thoughts on the subject

aka Rod Rees’ Vision of Utopia:

·

A utopia would be a perfect meritocracy where talent and effort are the

sole determinants of success and of position in society. Not something most of

society would embrace. I suspect (and I’m no biologist) that humankind has a

pre-disposition to promote the pan-generational success of the family for the

simple reason that by doing so the long-term propagation of the family’s DNA is

enhanced. This is why inheritance of wealth and status looms so large in human

history (most wars have been fought to ensure the survival of one ruling clan

or another). A utopian society would render this scramble to hereditary success

obsolete.

·

A utopia would be a society where you could believe and act in whatever way

you chose as long as these do not impinge on any contrary/conflicting beliefs

or actions espoused by other members of society. Of course, this is flies in

the face of politico-religious reality. Politico-religious systems are

evangelical in nature: you’ve only to see how avidly elections are fought to

recognise that. A politico-religious system wants/needs adherents and the more